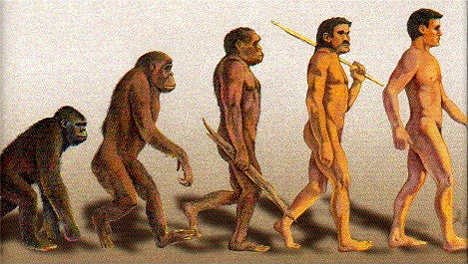

If the Big Bang Theory is science’s answer for the origin of the World, and a “Primordial Slime” or protobiont is it’s answer for the origin of Life, then the Theory of Evolution is science’s answer for the origin of Man.

The literature about Evolution may be vast but the literature based on Evolution is even more tremendous. Books have been written that specialize in evaluation of other books and articles written about Evolution, and so the theory itself has spawned meta-theory, a metaphysics of the metaphysics, one could say. So when we here discuss Evolution, we must be aware that many people have been down this road before. We must not criticize this idea too quickly, and I will try to present it accurately. We must not read more into it than what is there, and we must make sure we include everything that is essential.

Part of this we have already done, by setting up the foundational theoretical science on which this theory is, at least indirectly, supported. Now I wish to do this the best way I know how, which is to go to History, and get from her what we can about the birth of this idea.

Water, Air, Earth, Fire?

The Origin of Evolution

Human evolution, that is, Evolution pertaining to homo sapiens, is loosely defined as the general belief that Man and the simians share a common, ape-like ancestor. Whether or not this is what the first fathers of this theory had in mind at all, and what the identity and whereabouts of the higher half of our genetics could be, are both subject, to say the least, to some debate. We ought to, therefore, distinguish what I will call general evolution, the idea of which has been around since at least the ancient Greeks, from the special type of Evolution about which we are presently concerned.

Simply put, general evolution, or evolution with a small “e”, known today as microevolution, is the belief that Man, as well as all the other living creatures on the Earth, change and adapt over time. Environmental conditions, as well as intrinsic or genetic mutation factors, contribute to alter the behavior and even appearance of succeeding generations of living things. This can be as global as frogs developing (greater) jumping ability, or as personal as you mutating your own self and appearance through focused physical and/or mental exercises. Microevolution does not account for new species, however, as all the alterations witnessed are special, that is, pertaining to the species. Evolution, capitalized, is known today as macroevolution, and is primarily that theory of Darwin and his immediate predecessors (and subsequent parrots), which claims that by these very same processes, plus the overriding premise that the strongest survive, are also established the variety and different types of living things.

Mystery School

The Pre-Socratics And Stoics

That evolution had its beginnings way before Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species is pretty much a unanimous consensus. Considering Western thought alone, while the Greeks of old had no real word for “evolution”, as far back as the Pre-Socratics several philosophers held the opinion that things could be reduced to a common element, and that the progression up the Scale of Being is due to a type of evolution. For Thales, it was the element water that formed the basis of living things, for Heraclitus it was fire, for Anaximenes it was the air. The atomists, like Empedocles, Democritus, and later Epicurus through Lucretius, held that atoms, or tiny particles, are the building blocks of not only all living things, but also all matter, all things with substance and dimensions.

Empedocles, undoubtedly aware of the single-substance theories put forth by his contemporaries, as well as those of his recent past, held that not just one, but all four primordial elements – earth, air, fire, and water – constituted the basis of Life, and that the measure of each in any creature determines what type of life it is. He used “love” and “hate” as metaphors for explaining the interactions of these elements. Parmenides, about whom Plato dedicates a dialogue, argued that that all things are but one thing, “the One”, and that all change is unreal and only apparent, a consequence of the way we interpret, and are mired in, time. All this before Socrates, and all of them probably ideas originating in Middle East.

Few Western thinkers before Plato discussed this evolution concept more specifically than Anaximander. Shortly after 600 BC, the sage from Miletus put forth his view that living beings gradually developed from a union of water with heat. He went so far as to offer the opinion that men came from other kinds of animals. His fragments are available only from historical accounts, many of which can be found here. It was his thought, or the remnants of it, that was really the first in the West to set out to do honest science.

Later the Stoics would follow the idea of certain of these Pre-Socratics, such as Anaximenes, and embrace the idea of an igneous air as the primary principle of Life. The Stoics associated this idea with a deity, and said this deity is Life itself. The development of this Godhead’s Life was for the Stoics identical with the progress and dissemination of Life in the World. They coined the term logos spermatikos, from logos, meaning word, communication, reason, plan, or (my own definition) “the way it goes,” and sperma, or the life-giving principle. As a whole this term signifies the little “spirits” (the term today is misleading) that animate living things:

From this originating Logos or Word come myriads of individual logoi spermatikoi, children seed-powers, each bearing within it the primal reason (logos) or fire of spirit. The Logos is One, but to fulfill the work of creation, of molding “gross matter into the things that are to be” there are countless minor logoi, indestructible seed-powers which “…are, as it were, spirits or deities, spread throughout the universe, everywhere shaping, peopling, designing, multiplying; they are activities of fiery spirit working through tension in its highest development. But the seed-power of the universe [Logos spermatikos] comprehends in itself all the individual seed-powers [logoi spermatikoi]; they are begotten of it, and shall in the end return to it. Thus in the whole work of creation and re-absorption we see the work of one Zeus, one divine Word, one all-pervading spirit”. [E. Vernon Arnold, Roman Stoicism]

This trying to come to grips with evolution arose from these early thinkers’ desire to find, as we are here, the origin of Man. Their treatment of the subject is collectively the West’s first real scientific inquiry into this anthropogenesis, or beginning of Man, the first attempts at doing research without direct appeal to the traditional beliefs, or the established gods of the Greek pantheon. More importantly, “gods” became replaced by “God”, a singular, if in the form of a first principle, or reason behind human existence. Some of these God-aliases used by the Stoics and Pre-Socratics were the Air, the Breath, the Boundless, the Infinite, the One, and the Fire.

By far the biggest debate amongst these early thinkers was not whether there exists a force responsible for Life, as all of them, in some way, took that for a given. Rather, it was the identity of this main principle that was the main point of argument. One says “water”, one says “fire” and so on, and were I a clever thinker in that age I would certainly and quickly offer you the existence of a substance, particle, or force that is the cause, or producer, of both, in this case, water and fire. Hence historically we see, after the lot of element-based causes are offered up, the appearance of indefinite causes, concepts, and conglomerates, like “the Infinite” or “the Boundless” (apeiron), “The One” (to en; to on), and so on. Yet, as different as all their solutions seem to be, all of them nevertheless postulate some essential particle, substance, or force. All resort to a Primary Principle of some kind.

We should pause at this point and ask whether this line of thought is, in itself, indicative of progress, and if it is any less other-worldly in its presumptions than Natural Law, or even the myths by which Poseidon is made to rule the seas and Hades the Underworld. That this Pre-Socratic line of thought is seen, by scientific historians, as progress, in the sense of theoretical advancement, is very true, but whether such historians are correct in their assessment is, for me, very debatable.

Despite the near historical and critical, yet totally arbitrary consensus that the Pre-Socratics and early Romans and their “prime stuffs” evidence the first real grasps at doing science, not too many commentators have bothered to explain how significant, or insignificant, such efforts were, or at least, how their methods or approach increased human understanding. It is laughable, when you consider the by-then existing intricate statues and crafts, monoliths and pyramids, metals and cements, to claim Man did nothing we now call “science” prior to 650 BC. Nor has much been written stating, for instance, that we gain nothing from, say, renaming Zeus “The Unknowable”, or by calling Prometheus “Gravity”.

Western thinkers are also fond of giving the Pre-Socratics credit for being the inventors of the scientific method, but they do so for the wrong reasons. Thales and his successors were truly the first scientists, but not because they rejected the gods. Rather, the true Pre-Socratic progress was in their showing that accepting gods, a God, or even no-God, makes little difference where scientific research is concerned. In fact, by far the most of these 800-300 BC thinkers, whether as metaphor or as actual history, believed in some form of the tales of the gods. Neither did they have any problem accepting the premise that the world is made to be, ruled, and ordered, by these gods. The Pre-Socratics were an advance, rather, because they wanted to know how, that is with what and by what means these gods might rule and order the world, a fact easily discovered by researching most of these early thinkers’ lives. The little we know of them is more than enough to show they were as much mystics as scientists. That so many of them were initiates in what have become known to us as mystery schools further proves this point.

In summary, every one of these early evolutionists were in agreement that there exists in this world a primary power or force that is ultimately responsible for the first generation of Life. The further elaborations of this idea of a “Prime Mover” or demiurge responsible for the logos, or progression of Life, have their origins in the works of Aristotle and Plato, respectively, although this logos has much in common with Vedic, Egyptian, and other Eastern thought, and likely has its origin in those places.

Plato

For Plato, the demiurgos or demiurge is the architect of the world. The word literally means a “skilled worker” and a philologist would tell you the root word demos means the populace, or the people, and that ergos means the act of producing something, or working, it is the concept by which we get the word “erg“, or a unit of energy. A demiurge, taken as Plato meant it, is the conceptualization of one part of the logos, or cosmic order meant to account for that creative process which begins and maintains the unfolding of being. The term also means, etymologically, “creator of the people”, a term pretty synonymous with the origin of Man.

The demiurge is merely a part of Plato’s God, yet the only part we can hope to comprehend, all the rest of Him being outside the realm of Space and Time. One important step in the development of evolutionary thought was Plato’s synthesis of two Pre-Socratics, specifically he combined the ever-changing world of Heraclitus with the never-changing world of Parmenides. Plato’s belief was that Heraclitus was correct in insisting that the phenomenal, or observed world is in a constant flux, but that Parmenides was also correct in that the things in the World of Ideas (idea), or of the Forms (eidos) are most real and never change.

This Platonic synthesis began a thinking of the world on the one hand as idea and the other as appearance, something we know today as dualism, and which has its opposite in monism. While for dualism there is a Real, which is actually an Ideal World beyond time and space, and also a phenomenal, or objective world within time and space, for monism the things of idea and the things of the phenomenal world are at base of the same substance. Plato, is in this sense a dualist, but because of the ideas of the Real World’s archetypal qualities, and their continued existence in the face of change, deterioration, and the ravages of time, what is most real, for Plato, are the Ideas, specifically the Forms.

Plato was also a follower of Pythagoras, and the Mysteries (probably Coptic or Egyptian rather than Eleusinian). His real inquiry into the nature of Life and its evolution only begins with the Dyad, or the first manifestation of reality from the unknowable Monad. He was really a mystic philosopher more than a scientific one, so whereas the Big Bang starts in obscurity, Plato starts too in a similar speculated unknown.

From this point of the onset of being, the first differentiation where the human mind can apparently go no further into the foreseeable past, Plato began his philosophy. He felt he had to go backward, or more precise to say, inward in effort to discover Truth that cannot be deduced by standard scientific inquiry, that is, deduced by the usual methods of things like cause and effect and observation. It would be fair to say Plato felt this metaphysics more important a quest than the doing of practical science, and indeed this is where the real questions begin. His examinations of the things of the natural world, more precisely their changing and transient nature, forced Plato to say that that what is most real is that which is ideal. So it is that we see the emphasis, in his teachings, about the ideas and the forms, which therefore occupied the bulk of his contemplation, is primarily a study of metaphysics rather than of science.

[n.b. Indeed, the higher levels of understanding the deity, in his time, many believed required initiation into Sacred Mysteries. While Plato was such an initiate, he knew his hearers were not…as most today still are not. He could not reveal whatever else he knew, whatever he knew, for this reason. If you are interested in this debated aspect to Plato start here and then maybe check out Proclus (here is Proclus direct) and if you feel brave try Helena Blavatsky on Plato here].

Plato believed that the origin of Man is the same as the origin of eros, or erotic, desirous love (as opposed to agape, or philos). In his Symposium (203a-204b) Plato, following earlier tradition, says this Eros is the child of the union of Plenty (or Abundance) and Want (or Need), penia and poros. Man, like Eros, is midway between idea and phenomena, sharing in both, but never quite part of either. Like the ladder in the Symposium, eros is never ending, human desire never rests. The best we can do is pursue wisdom, make it the object of our desire, yet even this is an endless climb. No matter how hard we, as human beings, try to arrive at the Truth, about anything, we find there is a higher rung upon which we have yet to step. We never reach the objects of our desire and we are, in effect, bundles of wants waiting to happen.

In Platonic terms applied to humanity, we desire more, and the best things we can desire are wisdom (sophia), knowledge (episteme), and love. The Good, Plato’s God, is the source of all these things and the logos as well, and this Good cannot be sought by empirical means, or even put into adequate words. Such a pursuit requires wisdom, a clearly mystical, rather than scientific mode of inquiry:

This knowledge is not something that can be put into words like other sciences; but after long-continued intercourse between teacher and pupil, in joint pursuit of the subject, suddenly, like light flashing forth when a fire is kindled, it is born in the soul and straightway nourishes itself. [Plato, Seventh Letter, 341 c]

True knowledge of what exists requires enlightenment. Science will bring you only probable facts, as since it is about perishable things any conclusions it draws are bound to change, or be incomplete.

Plato will undoubtedly arise again later. He is claimed by scientists, metaphysicians, and scientists as a part of each of their histories. But he is not quite the scientist as was, say Aristotle.

Aristotle

Alexander the Great’s tutor Aristotle, it is well known, referred to human beings as “featherless bipeds“. A consequence of his classification system, this definition was for him as tongue-in-cheek as it is for us today. Like his teacher Plato, Aristotle believed in a World of Forms, Ideas that may be remembered or recalled, and by virtue of which any learning at all can take place. This process or recollection Plato called anamnesis, or “without forgetting”. But, as the common interpretation goes, while Plato was convinced that human beings are born with some knowledge, known today as innate or a priori knowledge, for Aristotle all knowledge comes via experience. This very “debate” recurs later when the so-called empirical philosophers – like John Locke and David Hume- took on the position of Aristotle, while the “rationalist” philosophers – like Descartes and Leibniz– echoed Plato.

In actuality, any in-depth study will show that this purported disagreement between teacher and pupil is not as large a divide as some scholars would have you think. Both Aristotle and Plato placed priority of the Forms over the transient things of our five senses, both thought existing, empirical things to be a combination of Form and matter, both considered learning a type of remembering, and so on. They are more like two sides of the same coin than opposites or rivals.

Psyche, Goddess of the Soul

At this point, we should recognize that Aristotle, in De Anima and elsewhere, was of the opinion that all living creatures have a soul. The Greek term translated by the Latin animus is psuche, or the psyche, more correctly, the soul (compare for instance nous, “spirit” or “mind”). According to Aristotle there are several types of soul arranged in a hierarchy, and each “higher” soul contains within it the aspects of the lower types well. Thus while some living things have vegetative souls, some appetitive souls, and others rational souls, even the highest rational souls are also, in part, appetitive and vegetative.

The real difference, evidenced in the psyches of mankind but absent from the minds of even the highest of the other rational creatures, is that while Man shares with these animals the ability (“has enough mind”) to learn tricks, follow orders, and be trained (nous pathetikos), Man alone can create, calculate, and synthesize and explicate information in a process we know as reasoning. Animals act solely on impulse, by instinct, through conditioning, or compulsion, and the amount of mind it has is so limited. The type of mind that Man has allows him to be a cause himself, to deviate from instinct. This is the poetic nature (nous poetikos) of Man which makes him unique, and it is a singular distinction of the human soul, alone enough, as I have argued, to define him as of a separate genus.

Incidentally, the Delphic Oracle’s proclamation that “Aristotle’s Biology holds the key to his Metaphysics” can be understood in the way we have just discussed and is important here. The nous poetikos that defines Man had to come from somewhere, and it comes, for Aristotle, from outside the body. It is not part of the human body and is imperishable. As for his teacher Plato, this special aspect of mind he thought to be something divine.

The Modern Influx

After the ancients, and we will get into even earlier thought when we discuss Creationism or Intelligent Design, the history of general evolution as to the origin of Man can be traced to the later philosophers and thinkers before Darwin and to a lesser extent Thomas Malthus.

Several of these thinkers were the Germans Johann Gottfried Herder, GE Lessing, and Goethe in and around the 18th Century. All took the historical perspective, and tried to trace the origin of Man as a part of their general outlook that there is some sort of consistency in Nature that links (Aristotle’s) Genera of Being one to another. Goethe, for example, studied the differences in the metamorphosis of plants. Schelling, Erasmus Darwin (by whose theory DNA was discovered and who said “all warm-blooded animals have arisen from one living filament… with the power of acquiring new parts”…and by whose genetics we get Charles…) Kant (who called differences of species by evolution “a questionable exercise of the reason”), and especially Hegel (with his expression of the Weltgeist, or World-Spirit), all had something to say about general evolutionary ideas. Erasmus Darwin especially, took this metaphysics to its highest expression yet, with the possible exception of the Frenchman Lamarck.

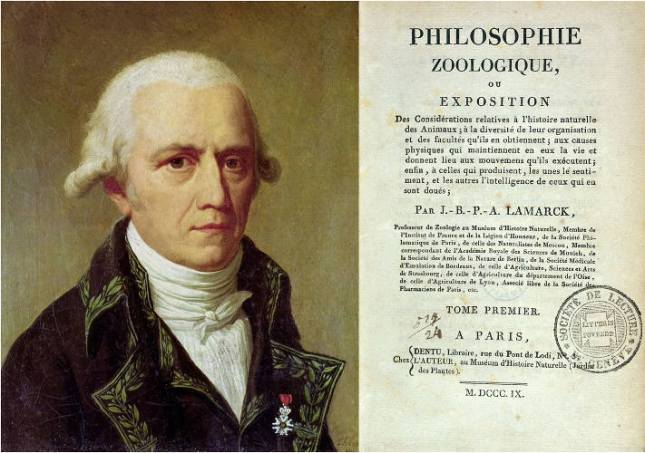

I reprint the following quote to some extent (found here at Wikipedia) because the importance of Lamarck (and to a lesser degree, fellow Frenchman Lavoisier) to the Theory of Evolution is still under-appreciated, and often misunderstood. While the similarities of Lamarck’s ideas to modern theory are obvious, it is in the differences that we will find the distinction between general evolution theory and the Theory of Evolution so-called since Darwin.

Lamarck stressed two main themes in his biological work. The first was that the environment gives rise to changes in animals. He cited examples of blindness in moles, the presence of teeth in mammals and the absence of teeth in birds as evidence of this principle. The second principle was that life was structured in an orderly manner and that many different parts of all bodies make it possible for the organic movements of animals.[25]

Although Lamarck was not the first thinker to advocate organic evolution, he was the first to develop a truly coherent evolutionary theory[27]. He outlined his theses regarding evolution first in his Floreal lecture of 1800, and then in three later published works:

1)Recherches sur l’organisation des corps vivants, 1802.

2)Philosophie Zoologique, 1809.

3)Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres, (in seven volumes, 1815-1822).

Lamarck employed several mechanisms as drivers of evolution, drawn from the common knowledge of his day and from his own understanding of chemistry pre-Lavoisier. He used these devices to explain the two forces he saw as comprising evolution: one force driving animals from simple to complex forms, and another force adapting animals to their local environments and differentiating them from each other. “He believed that these forces must be explained as a necessary consequence of basic physical principles, favoring a materialistic attitude toward biology” (ibid.).

Were I to summarize Lamarck I would say that he did what Darwin did before Darwin did it. That is, whatever is good, or better to say truest, in Darwin’s thought, is a direct consequence, if not outright theft, of the ideas of Lamarck. He was, first of all, the pioneer of the study of genetics, specifically the transference of traits in living things from one generation to the next. Lamarck also was the first to claim that while beneficial traits are for the most part retained, undesirable or maleficent traits tend to disappear in later generations.

Unfortunately, though. Lamarck could not explain the origin of new species. He could by his theory, like Darwin, account for, say, an aardvark developing a long snout over time to more readily get the ants and small insects it likes to eat. But also like Darwin, he could not explain why all, let’s say opossums, did not become aardvarks. Neither man’s theory can explain new species effectively.

Also, much of Lamarckianism, like much of Darwin has been, justifiably or not, disputed. Lamarck’s theories would say, for instance, that a child of a person who throws a baseball for a living would be better at throwing a baseball than an average person, because his father and his grandfather did the same. This seems true to me, and evidenced in the professional sports world, the acting world, the military, and so on. Current research, though, has objected to this, on grounds, for example, such as the fact that even though the parents of a child use the toilet, that child still needs to be taught how to do so.

That this objection to Lamarck’s genetic inheritance claims could be a category mistake has so far gone unsaid. I think such objections are a leap at best, at worst a caricature. Lamarck never denied that the things of Life need to be learned, what he asserted was that because of their ancestral history some people pick things up faster than others. As a scientific theorist, his idea stands strong on general evolutionary grounds. In real life, basketball players do produce children better at basketball than the average, even they must first be taught how to dribble and shoot; a politician’s son has better odds at becoming elected, even if he must learn to speak properly; a father who does manual labor will produce a child more prone to muscular development and amassing physical strength, assuming he is active. More than that, one could extend the theory to say that the further a family tree can trace common duties and jobs,the further the specific qualities for them are enhanced. The potential becomes extended.

Yes it is true some active geniuses have children who amount to nothing more than lazy dullards. The current Theory of Evolution diverges from Lamarck by denying hereditary potentialities. Yet this Evolution creates new species by the same process whereby Lamarck explains differences only within a species, and by this adaptation [sic.] contemporary scientific theory thinks it has advanced past Lamarck.

Today, attributing difference in genera to environmental adaptation has the result of a belief in Nurture over Nature. This is, as we will see, the essence of Darwinism, that particular branch of evolutionary thought of our time. It also is VERY important to note the differences here between Lamarck’s evolution and Darwin’s Evolution. Lamarck’s theory lends real support to the sciences involved with improving the stock, of the best more likely to produce the best. Darwin’s is more amenable to those special interests that want to claim everyone equal at birth, differences amounting to culture and upbringing. As the old debate goes, some will say you can take a child of the worst and poorest background and genetics, and raise her from birth in an affluent house with all the things necessary for a successful life, and despite her genetic makeup she can become Governor. Others will say you can take the best genetics and breed a similar child in the very same home and end up with a good for nothing ne’er-do-well, criminal, or psychopath.

The question is: are they saying the same thing?

Next stop, Charles Darwin himself, or call it, the reason for the madness.